IN DEFENCE OF HONJOZO

Turbot, I love it, when I can afford it. Scallops too, overwhelmed by a tidal wave of foaming nutty butter in a pan but sometimes I just crave a simple piece of grilled mackerel with a squeeze of lemon, rather than a truffle beurre blanc sauce. And the same applies to my approach to Sake drinking.

In fact when it comes to Sake, I’d probably like almost as much mackerel as turbot if I’m being honest. But what on earth am I on about? Well I’d like to talk about Honjozo, the humble mackerel in this analogy. I want to fly the flag for Honjozo which can be every bit as rewarding a drinking experience as anything Ginjo in my opinion.

Don’t get me wrong, the skill, time, patience and downright obsession in making great Ginjo is borderline fanatical and I have plenty of sub-60% seimaibuai labels and entries in my Sake scrapbook, with glowing reviews.

But everyone loves an underdog, right? Well it seems not so much these days.

In the worst year for Sake since the 60s when presumably everyone was getting their highs by other means, 2018’s shipping stats saw most Sake grades down year on year, with Honjozo recording a massive -10.8%.

I guess the kids don’t want the kind of Sake that grandpa used to sup, now it’s all about the Ginjo and very much Junmai. And that just ain’t right.

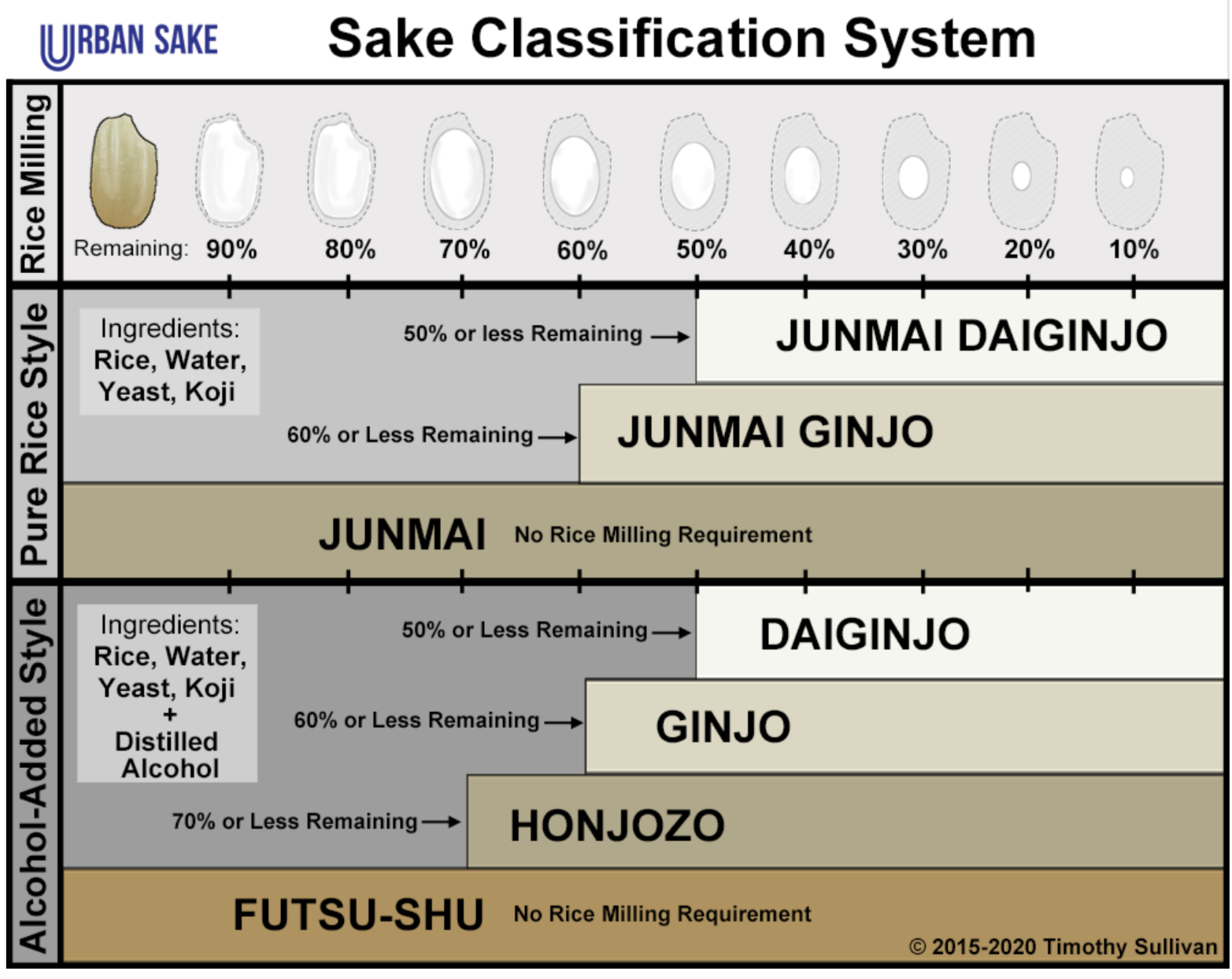

But before I get all preachy about Honjozo, now is probably the time to simply lay out all these grades for anyone reading who is thinking “What’s this guy on about?”.

Tokutei-meisho-shu: Special Designation Sake Grades

Courtesy of Timothy Sullivan & UrbanSake.com

OK, hopefully that will help.

So back to my diatribe and I believe Honjozo (“hapless Honjozo” as John Gauntner recently described it in his informative YouTube - see LINKS below) has suffered unfairly at the mercy of various powerful market forces, but offers three very compelling reasons to buck this trend: heritage, value and personality.

Let’s start with heritage.

In the last 100 years there has been more innovation in Sake than in the previous 2,000 (yes, Sake in some form or other is that old, and in very recognisable form at least 1,000 years old).

In 1933 vertical milling machines allowed rice to be polished consistently and accurately like never before, opening the floodgates for new flavours and aromas. Just over a decade later, new yeasts were isolated including #7 (still the most popular in our current century) in 1946 and #9 in 1953, a real belter of a yeast for Ginjo Sakes. These yeasts, along with further technological advances, paved the way for the fragrant ‘n fruity 80s Ginjo boom.

So, prior to the early 1930s, the breadth of the Sake offer was significantly narrower than it is now and although Honjozo is itself milled to 70% or less, it’s a lot closer to the Sake heritage of the previous 1,000+ years than those with a seimaibuai somewhere south of 50%. For me, there’s a place for both in my fridge, side by side, to embrace the future of Sake whilst being respectful of where that future has come from.

And by the way, the post-war era Sake rice was by and large polished to a rustic 70% or 80% which tasted ambrosial after the additive rich firewater they had all been drinking in those turbulent years. Has all this low milling spoilt our palates? In decades to come will a 50% Daiginjo seem “rough” because we’re all hooked on 30%? I hope not.

Trends are a powerful influence and Ginjo is a great example that has yet to fizzle out. Yet so is the demand for Junmai, but why? It bucks the trend of the delicate aromatic Ginjo categories with its full and rich offering.

Well, there’s an attraction to the purity - the 純 of 純米 - that is ingrained in the Japanese mindset. Junmai translates as pure rice sake, meaning that it is made just like the other grades of Sake but without the addition of brewer’s alcohol.

Yet this addition isn’t for economic reasons within the special designation Sake grades. In fact, far from it. The amount that can be added is strictly controlled by law and more importantly, the alcohol aids the Sake’s organoleptic properties by dissolving and releasing into the liquid previously unavailable aromatic compounds.

Honjozo always has this added alcohol which essentially moves it one step closer to a lighter and more fragrant drinking experience. So what it lacks in Junmai purity, it makes up for with fragrant attributes, bordering on Ginjo territory. You’d think that should have some appeal.

One more thing in support of Honjozo, perhaps a little fanciful but for me it’s a biggie. I was reliably told on my last trip to Japan that many Toji will claim their preferred Sake from within their own portfolio is their Honjozo (I had to stifle a smug ‘told you so’ as I agreed in that particular brewery where I heard it). For me, that’s a massive fat tick against Honjozo, kind of all you need to know right there. Case closed?

“Hapless” Honjozo

Probably not so let’s move on to value.

As Timothy’s chart shows, the undeniable fact is that Honjozo, at 70% or less seimaibuai, is regarded as part of the esteemed Tokutei-meisho-shu family. Sure, it’s not at the top of the premium tree but nor is Junmai and on paper it should outclass Junmai actually.

In the scheme of Sake history, 70% is big news (taking some eight hours for milling) and in the right hands, magic can be performed. So it’s even possible to have 90% polished Junmai that tastes great (and I did, from Senkin Brewery, at the weekend) made from table rice. These guys are good.

Now you could save a few $s and still buy a very decent Futsu-shu which would be a fine beverage indeed. The likelihood is it would come from a large production facility. There’s not so much artisan Futsu-shu out there and I’d rather support the small producer making the Honjozo.

Spun the other way, spend a little more and you’re in Ginjo country but at the bottom end (sure, bottom end of very very good) and if you can live with this, go for it. But isn’t that like buying one up from the cheapest wine on a restaurant’s menu? Or buying an entry level BMW when in reality you want the X5?

But do buy something! All I’m saying is that one added benefit with Honjozo is that it makes no exception to quality but it’s also quality at a price that generally is somewhat gentler on the credit card.

Tokubestsu Honjozo 特別本醸造 - this one polished to a Ginjo-esque 55%

Finally, to perhaps the most persuasive argument of the three: personality.

Honjozo for me is full of it, bolstered perhaps by the vague Tokubetsu (“special” Honjozo) category within a category allowing for upgrades like more highly milled rice (in the majority of cases) or a special rice (normally 100% proper Sake rice), or something else deemed Tokubestsu enough. It’s a grey area of Sake legislation. And to confuse us drinkers more, it doesn’t legally have to be declared why it’s special on the label.

What it does mean though is that Honjozo, like Junmai to some extent, has some wriggle room to be both traditional style Sake and more modern style Sake. A Honjozo could become Tokubetsu and be milled to Ginjo or even Daiginjo levels. But it does not need to feel obliged to compete with these top grades on delicate aromas and subtleties, leaving you with Ginjo classiness fused with Honjozo honesty and rustic traditions, at a price that will make you smile.

Also, Honjozo lends itself well (yes, Junmai too) to the traditional Kimoto or Yamahai yeast starter methods. These methods (another post needed) are the precursor for today’s modern faster Sokujo Moto process and, sadly, only make up for a tiny part of the overall market but they are a portal to Sakes past, and I’m all for that.

Yamahai followed and simplified Kimoto but both share a wild, gamey characteristic in their Sakes. Yamahai a little funkier, Kimoto a bit more ‘tart’ but both allow Honjozo to broaden their flavours. I really like the way these artisan methods can be maintained in today’s more technologically advanced production market.

Yes, there are Yamahai and Kimoto Ginjos out there which is clever brewing indeed and I look forward to emptying my piggy bank to be able to afford them but in reality, the humbler Honjozo and Junmai have a better fit.

Making highly milled Yamahais and Kimotos is a bit like using a pestle and mortar to make a silky Jerusalem artichoke purée when in reality it can be a 5-second job in a HK$12,000 Thermomix. But to make a delicious rustic chimichurri, hand me the pestle.

The very fact that Honjozo can be anything from funky-gamey to fragrant-classy means that it’s a great food Sake. You can probably pair one or another with pretty much most Japanese and Western dishes which is something you wouldn’t want to do with most Ginjo. This makes me smile. And hungry.

Don’t forget, warming Honjozo is also a very viable option. Instantly you’re adding a second option to how you appreciate each bottle you’re buying, and this also helps with food pairings. This is truly brilliant stuff.

So there you have it, my reasons to get behind Honjozo.

Also decent as Nigori - there’s no end to Honjozo’s talents

If you’re convinced to give it a try then my work here is done. But whatever you do, the key thing is to buy Sake. We can’t rely on the new drinking generation in Japan, it isn’t so much into boozing. And when they do booze, beer is the weapon of choice.

In terms of volume, national production of Sake has fallen since the heady days of 1973 by something like 75%. Ginjo is keeping things alive, particularly Junmai Ginjo, but we can’t yet see what the impact of the virus will be and postponed Olympics.

I’m way beyond my mental word count so no time for a Honjozo review but we don’t need one. It’s great. Try it, and try lots of it.

FOOTNOTE:

In this article, I’m using “Ginjo” as a catch all for the top 4 categories of Tokutei-meisho-shu, namely:

- Daiginjo

- Junmai Daiginjo

- Ginjo

- Junmai Ginjo

(Just saving paper).

Data sourced from: https://www.nta.go.jp/index.htm

QUICK GLOSSARY:

Honjozo 本醸造: Sake made from rice at a polishing ratio below 70%

Ginjo 吟醸: Sake made from rice at a polishing ratio below 60%

Daiginjo 大吟醸: Sake made from rice at a polishing ratio below 50%

Junmai: Sakes made with no added alcohol are Junmai, the only ingredients are rice, water and Koji mould

Seimaibuai: The percentage of rice remaining after the polishing process compared to its original weight (so a 60% seimaibuai reflects that 40% has been polished away)

Tokutei-meisho-shu: Special designation Sakes, variously categorized but all meeting various stringent guidelines

Toji: Master Brewer with ultimate responsibility for brewing and the leadership of the brewing team

Futsu-shu: Every day “table Sake”, but still delicious and accounting for by far the lion’s share of Sake drunk domestically in Japan

Tokubetsu 特別: Simply means “special” and identifies that a special production process was applied to a Junmai or Honjozo category Sake. More often than not it designates that a lower rice polishing rate than required took place

Kimoto 生酛: Kimoto is a style of Sake that uses the original yeast starter method laboriously created using long paddles to promote natural lactic acid development (takes 4 weeks)

Yamahai 山廃: Yeast starter method developed after Kimoto allowing for natural lactic acid production but without the labour of Kimoto’s long paddles (takes 4 weeks)

Sokujo Moto: Modern “fast” yeast starter method whereby lactic acid is added directly to the yeast starter allowing the process to finish in 2 weeks

LINKS:

John Gauntner’s YouTube The Effects of COVID-19 on the Sake Industry in Japan can be viewed here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=nsgMSeil9Gw

Thanks again to Timothy Sullivan’s wonderful ‘Sake Classification System’ chart from the ever-informative www.urbansake.com