THE DATING GAME

This article takes a curious look at the significance of the bottling date with particular emphasis on Namazake.

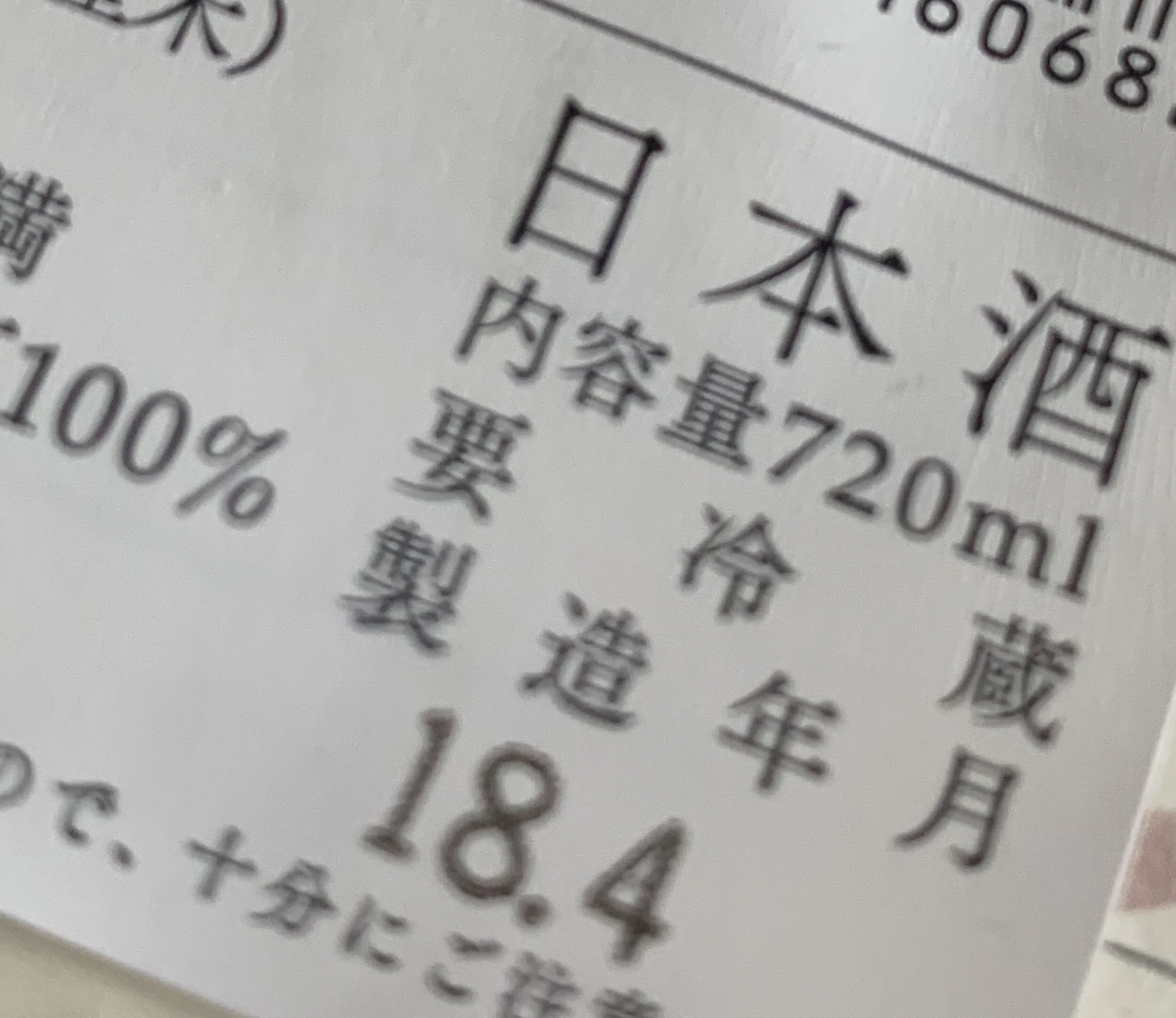

Grab a Sake bottle from the fridge and amongst the mass of Japanese characters on the back label there are a handful of numerals. Normally there are three or four that stand out, separated by a full stop, reflecting the bottling date of what you’re holding. In this case 19.10 in the bottom right hand corner (Year.Month – so October 2019). Other bottles do this using BY (bottling year), but I’ll save that for another time.

For those of us outside of Japan, Namazake (or Nama-zake, or just Nama, but always 生酒) can sadly be a bit hit and miss, in my opinion at least. These Sakes can be created from any one of the premium (Tokutei-meisho-shu) or basic (Futsu-shu) Sakes. But, the common differentiator is that they are all unpasteurized to some degree in that they will have missed at least one, if not both, of the regular Sake production’s pasteurization stages.

Quality, gold standard importers bringing Namazake from Japan to thirsty markets around the world make the effort (and absorb the refrigeration costs) of importing this style of Sake to be enjoyed as the Toji intended. So let’s quickly agree, or at least explore, what Toji-san wants us to experience.

The key is in the Japanese kanji “生” – Nama. The various meanings of 生hint at what to expect from a Namazake, namely ‘live’, ‘raw’ and ‘fresh’. And to keep it so, it should always be stored out of direct sunlight in a refrigerator to prevent deterioration, spoilage and discoloration. It’s a very fragile and sensitive Sake.

In its unpasteurized state, the Sake is alive and active and although the majority of yeast cells, enzymes and other micro-organisms are trapped during pressing, a residual population lives on, and it’s this little splinter group that gives Namazake its unsullied personality.

Trawling through a few reliable sources, it seems the Sake movers and shakers agree that Namazake has a fresher, vibrant, bright (possibly sharp) taste and fruitier aroma, versus the more subtle and softer pasteurized Sakes’ credentials. It is youthful, fragrant and untamed. Some describe it as fizzy and spritzy. You’re getting the picture I’m sure.

Nihonshu Oendan was started up in 2015 and works with artisan brewers across Japan doing all the right things, respecting tradition and the heritage of the regions. I first tasted their gorgeous Noto at Sake Central here in Hong Kong (definitely one of the importing ‘Good Guys’) and the distinctive family of labels remained ingrained instantly in my memory. Twenty years working in Marketing and I’m still a sucker for a good label.

These are my kind of Sakes – not only are they all Namazake, they are also unfiltered, undiluted and made without the addition of brewer’s alcohol. So, seeing a nice selection for sale in London in February I was already reaching for my wallet before sliding open the door to the chiller cabinet. And, imagine my smugness at the promotional discounts being rung up at the cash register a few moments later. Little did I know I was about to partake in a Namazake experiment.

Why was I saving 70% on the Noto and 50% on the Kamogata? Well, arriving back that evening at the hotel, my heart sank when I noticed the bottling dates showed these Sakes to be over 22 months old. Hindsight is a wonderful thing.

But here is the joy of tasting Sake, and a great example of just why I would always consider the Sake industry ‘rules’ more as ‘guidelines’. These bottles had at least been well kept and refrigerated, so I was keen to see what lay inside.

For both Sakes I didn’t write anywhere in my notes any of the Nama-defining descriptors mentioned earlier, nor did I come across the anticipated exotic fruits (in fact I noted down a presences of dried fruits). However, I did detect some citrus freshness still in the Kamogata but both Sakes were far from tired or flat.

A savoury meat stock had taken over, umami was in residence and as the bottles warmed to room temperature more than a hint of lactic notes ensued, some mozzarella creaminess and even a whiff of old school custard powder.

I loved them.

The point of all this idle reminiscing? Don’t be afraid to experiment. I was hungry for lively Namazakes to match up to my earlier Sake Central encounter but instead got a more robust adult Sake experience. But they were good and it gave a real sense of the great art being achieved by the Nihonshu Oendan crew (and all enjoyed at a much better price, win-win!). Their Sakes are good young or (unavoidably) older. Great job.

Within the Sake industry there are always exceptions. Many would say Namazake is best consumed as quickly as possible and for the most part I would agree. But I have also been reliably informed that drinking Namazake up to 12 months is completely within reason.

My message today is good Sake is good Sake. If it’s kept well, you’re probably still in for a treat, or at the very least a surprise. But either way it’s all a good learning journey.

Having researched and now written this article, the Namazake spectrum feels far larger than I previously thought. For example, I uncovered Sekiya Brewery’s Houraisen brand that includes their Wa Aged Junmai Ginjo Nama “Harmony”. Purposely aged Nama? Check out the non-Nama descriptive language used by San Francisco pioneers True Sake in their tasting notes:

“The nose on this 12-month aged unpasteurized sake is a gentle collection of peach, apple, plum, red apple, and blueberry aromas. Why age a Nama sake? To get a feeling and flavor profile such as this Junmai Ginjo. Instead of being jagged, edgy, and brash the aging of this Nama creates a more comfortable feeling of the fluid. It helps the flavors meld better to produce a juicy yet smooth and round brew that is like a mellow Junmai Ginjo. Look for hints of green apple, grapes, blueberry and lots of pear as it warms in the glass. Milled to 50% this is actually like an unpasteurized Daiginjo, which makes the drinking experience all the more ethereal. This Nama is not bulky or sweet it is smooth and in the grove.”

If I’ve confused you as much as I’ve confused myself then I make no apologies as this is what makes Sake so interesting and enchanting. For once, it’s quite nice to take one step forwards and two steps back. Plus, it also gives me a great excuse to try again that Noto back at Sake Central later this week!

FOOTNOTE:

I should say to readers with some Nama knowledge that for the purposes of this article I’m grouping all three types of unpasteurized Sakes under the general heading of Namazake. We’ll go into detail another time around the idiosyncrasies within.

QUICK GLOSSARY:

Namazake: 生酒 (生:raw, fresh, or living; 酒:sake) – in short, unpasteurized Sake

Toji: Master Brewer with ultimate responsibility for brewing and the leadership of the brewing team

Tokutei-meisho-shu: Special designation Sakes, variously categorized but all meeting various stringent guidelines

Futsu-shu: Every day “table Sake”, but still delicious and accounting for by far the lion’s share of Sake drunk domestically in Japan

LINKS:

Sake Central

S109-S113, Block A, PMQ, 35 Aberdeen Street, Central, Hong Kong

www.sake-central.com

@sakecentral

True Sake

560 Hayes St, San Francisco, CA 94102, USA

www.truesake.com

@truesake

Nihonshu Oendan

www.artofsake.com